Ladies of the jury: the long fight for equality on juries

In my post on My Inspiration for Death at Crookham Hall, I mentioned that despite the Representation of the People Act of 1918, a significant milestone in the suffrage movement, a third of the adult female population in Britain still didn’t have the right to vote.

The fight for equal representation was far from over, and this was certainly true when it came to women serving as jurors. The repercussions of this inequality are highlighted in Death at Crookham Hall.

Although women had played a role on juries since the thirteenth century, it was in a specific capacity; in this century, ‘matrons’ were first recorded. Matrons formed a special class of jury with the task of ascertaining whether a woman found guilty of a capital crime was pregnant. If a woman was pregnant, her execution was delayed.

After the Representation of the People Act 1918, women could sit as jurors. But in the same way a property requirement restricted the number of women eligible to vote, it also restricted who could sit as a juror. Under the act, women had to occupy property worth at least five pounds per annum to qualify for a vote in parliamentary elections. However, under rules dating back to 1825, you had to own at least twice as much to qualify as a juror.

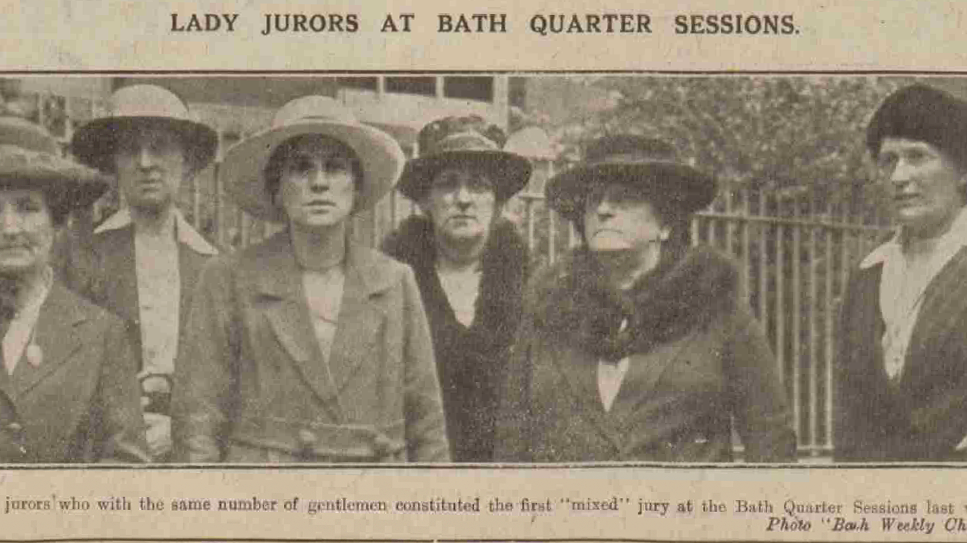

The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 removed the bar on women serving as lawyers, judges or magistrates. The act helped to open up the civil service to women, who could sit on grand and trial juries for the first time.

However, even though women qualified, it didn’t mean they’d be summoned by local officials or selected for a case. In serious criminal trials, lawyers could remove several prospective jurors without giving a reason. And the trial judge had the authority to order an all-male jury. Some judges would even invite women to excuse themselves if they deemed the trial might prove too shocking for them.

As a result, it was a long time before any women served as jurors despite changes in the law.

In April 1920, several women were summoned to the Colchester Quarter Sessions. But it wasn’t until 29 July 1920 that women finally took their place in the jury box at the Bristol Quarter Sessions for the first criminal trials ever to be heard by a mixed jury in Britain.

.

Sources for this article included:

https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/blog/how-women-finally-got-right-jury-service/

https://first100years.org.uk/1481-2/